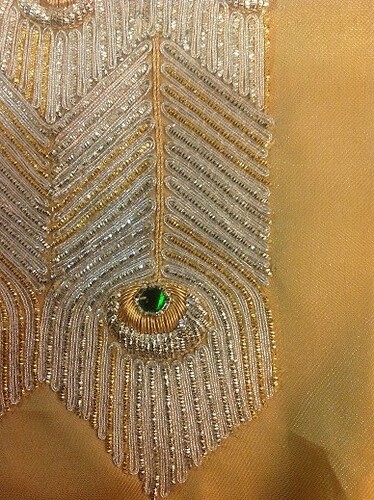

Photos of the sample have arrived from Indian Embroiderer MkII, and it’s near-as-dammit perfect!

I love that not only do the two photos below represent a very, very good approximation of the Peacock Dress itself, but that they also look like pictures I could have taken of my own version of the embroidery. When the email arrived, I screamed maniacally at a stormy, lightning filled sky, “MWAHAHAHAHA!! I HAVE SUCCESSFULLY CLONED MYSELF!!! IT LIIIIIVES!!!” And of course it looks like both the original dress and my embroidery because I provided pictures of both for reference, as well as an actual sample of my embroidery that I sent to India in the mail. (The difference, of course, is that they will have done this in about ten minutes flat, whereas I would have taken days.)

The new sample from India

The next step is materials; Sweta is having trouble tracking down just the right bits and pieces, and doesn’t yet know where to find beetle wings. Ebay is your friend, I shall tell her….

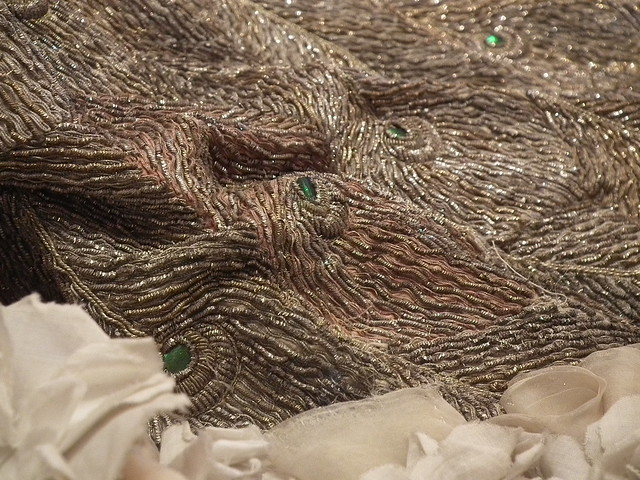

Pink feathers

Meanwhile, there is also progress on solving the mystery of the pink feathers. If you recall, the original dress features just a few feathers, randomly distributed over the skirt, that look reddish from a distance, and pink up close. What is the cause? It’s not all that easy to see in a photo, but what’s different here, in the feather in the center of this image?

When you look a lot more closely, it appears as though the passing thread (the white thread with a metal strip wrapped loosely around it in a stripy-looking effect) is the culprit – it’s this that’s pink.

Why does this level of detail interest me? Because I’m not producing a replica of this faded, tarnished beauty, but a replica of the dress that left the Worth workroom in late 1902. The pink caste seems to be evidence of something decayed, something that looked different when the dress was first produced, and I want to know what it was that the embroiderers intended so that I can reproduce it accurately.

Nowadays visitors do marvel at the Peacock Dress, gently lit in its glass case in the bowels of the Hall, but I want to tell them that they don’t see it at all! What they are seeing is a pale, fragile, tired, heavily altered, elderly shadow of the dazzling dress that Mary Curzon wore on the night of January 6th, 1903 at the Coronation Ball in Delhi. I want to take them back in time.

Previously, I have had a goldwork expert at the British Museum tell me that he could not draw any definitive conclusions, but suspected that it might not be the right shade of pink to indicate copper content. But this week, I have had an email from a Senior Textile Conservator at the V&A:

“…it is difficult to tell if the core thread is pink or if it is just the metal foil that is wrapped around it.

“It is possible that the metal has tarnished and the tarnish has a pink caste, I have seen that before and presume the effect is caused by the alloy used – and it maybe the tarnish has discoloured the core thread.

“It is very hard to say anything with certainty without being able to examine the piece. If it was possible to have the metal foil analysed that may provide an answer, as it could be that one particular batch of metal thread has a higher copper content.”

Well, I would love to have a little piece of the metal taken from the dress and analysed, but judging by the amount of time it took to convince the Hall staff to open the glass case and let me even look inside (ten months), I think it’s highly unlikely they’ll let me take anything away from it. (But there is one person reading this who works there – so I await her opinion!)

Since I have seen the dress in person, I would say that whatever is in that metal wrap is indeed what has discoloured the thread. I looked very closely at the time and satisfied myself that it was white thread discoloured to varying shades of pinkish hue in different areas, and not a pink thread. That shows in the photo, but of course the conservator wouldn’t want to draw definitive conclusions on a photo alone.

So I would go with the alloy being the culprit. Secondly, those metal threads were made in a number of recipes; by this date various alloys were being tried out to reduce costs, and it was common for a gold or silver outer appearance to disguise a copper core. (Reference). It’s perfectly possible that different batches might have been employed on different parts of the dress, given the sheer quantity of embroidery on this thing.

HOWEVER. Why would a different batch be used for specific feathers, dotted randomly around the dress? I can see one embroiderer working on a section with a different batch of passing thread, and the appearance there decaying slightly differently, leaving a patch like a large red wine stain, but this is a different batch being used for specific, individual, clearly defined feather motifs, beginning at the top of the feather and ending at the bottom. Surely this is deliberate.

And if it is deliberate, it further indicates that not only was the alloy different, but the appearance of the thread was different even then, and was used for effect. And therefore, I don’t think it’s unreasonable of me to have concluded that some of the feathers may have been made with a copper passing thread – or some other metal that has decayed to pink. In the absence of any alternative suggestion from the British Museum guy, even though he thought it wasn’t copper, and in the absence of any other option in goldwork supplies on the market today (short of green, blue, etc), I’m going to instruct the embroiderer to make every tenth feather or so with copper passing thread, and call that a reasonable final assumption.

Does my reasoning make sense to you, research boffins reading this, or do you think this is too much of a leap?

This *is* my own embroidery from 2011.

This is so beautiful I want to cry and create x

Could it simply have been rose gold which was used to create the pink feathers or is that too obvious? I believe that’s pink because of slight copper content.

Yes, it could well be rose gold – I’m thinking that too these days. Must investigate…

I’m going to try my own version of this for my future wedding dress I’ll send you pictures when it’s done